ad vcely

tl;dr - minishrnutí

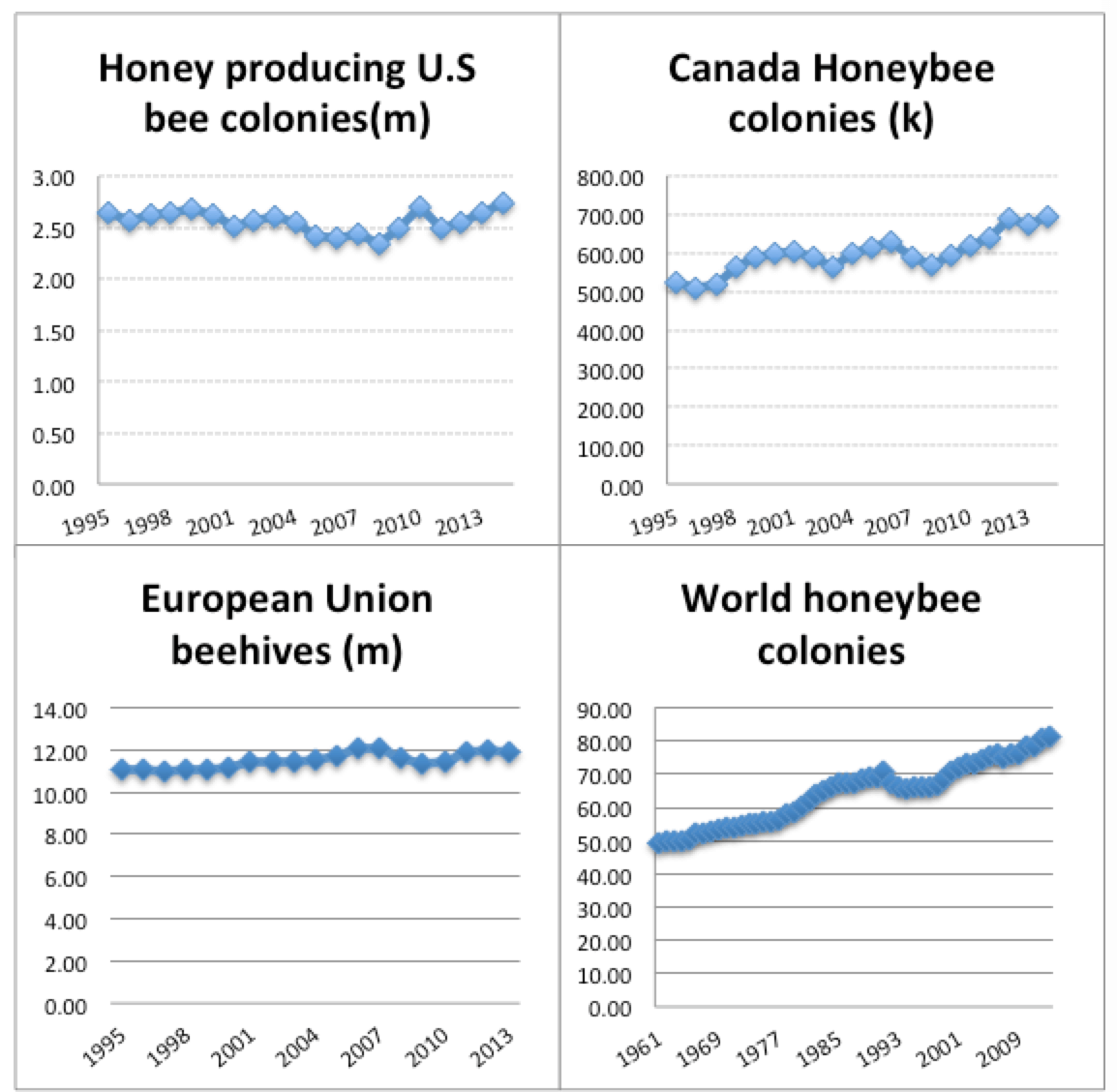

internetova vlna obav o vcelstva se zvedla s odumiranim vcelstev v usa, coz uz neni v takovem meritku aktualni, v evrope s timhle masovym odumiranim problem nebyl. z pohledu na data nevyplyva, ze by populace vcelstev byla ovlivnena varoazou, oteplovanim, pesticidama, nejvetsi zaznamentelnej vliv je celkovej pocet jednotlivejch vcelaru. ackoliv populace vcelstev v zap. evrope&usa v poslednich 50 letech stabilne klesa, globalne naopak vyrazne vzrostla (60% za poslednich 50 let) a zrejme diky tomu vzrustu jsou vetsi kazdorocni vykyvy. v usa minuly rok ztraceno 44% vcelstev (leto 16, zima 28), v evrope za sezonu 14/15 prumerne pres zimu 17% (coz je akceptovany normal). ruzne skupiny vedou souboj o interpretaci tohohle problemu, s cimz souvisi otazka neonikotinoidu - v evrope nyni zakazane. je mozne, ze na bezna vcelstva jejich pouziti z pohledu konvencni produkce nema fatalni dopad, protoze jejich ztraty (zapricinene soubehem mnoha faktoru) se daji vykryt rozdelovanim ulu. dopad to nejspis ma na populace divokych vcel, cmelaku, atd.

nejvetsi break v populaci vcelstvev byl zaznamena v evrope po rozpadu vych. bloku (7 mil. kolonii zmizelo), krome ceskoslovenska a madarska, kde nebyl rozdil. podivame-li se z pohledu obchodu s medem, pak tam, kde se nejvice obchoduje (import+export) je zaroven nejvetsi ubytek vcelstev (nevyplati se je mit na med), a zaroven zrejme dochazi i k nejakemu falesnemu oznacovani importu za domaci (svedsko, belgie), jelikoz jim vychazi uplne nerealna produkce na jedno vcelstvo.

data z uk ukazuji, ze nyni dochazi k narustu poctu vcelaru a s tim i k narustu poctu vcelstev. urcitym zpusobem tedy internetove-medialni propagace prispiva k obnoveni zajmu o vcelareni, ale za pouziti mylnych argumentu. (= upadek poctu vcelstev je spise upadkem kultury vcelareni, nez nejaky jeden novy cinitel. redukce biodiverzity vlivem monohospodareni se tim samozrejme neresi, mame radove nizsi pocet vcelstev na km2 nez v pousti kalahari)

výpisky (studie na konci je nejlepší)

Deciphering the mysterious decline of honey bees

http://phys.org/news/2016-05-deciphering-mysterious-decline-honey-bees.html

výpisky (studie na konci je nejlepší)

Deciphering the mysterious decline of honey bees

http://phys.org/news/2016-05-deciphering-mysterious-decline-honey-bees.html

In 2006 beekeepers in the United States reported that a mysterious affliction, dubbed Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), was causing widespread die-offs of bees. In colonies affected by CCD, adult workers completely disappeared, although plentiful brood (developing bees) and the queen remained.

…

Scientists now agree that CCD was likely caused by a combination of environmental and biological factors, but nothing specific has been confirmed or proven.

CCD is no longer causing large-scale colony death in North America, but beekeepers all over the United States are still reporting troubling colony losses – as high as 45 percent annually.

…

While beekeepers can recoup their losses by making new colonies from existing ones, it is becoming increasingly costly to keep them going. They are using more inputs, such as supplemental food and parasite controls, which raises their operating costs.

…

Studies show that when bees have access to optimal nutrition, they are better able to deal with diseases and pesticides. But intensive farming and urbanization have reduced the amount of readily available forage that bees need to thrive.

…

Ultimately, however, making our society more pollinator-friendly will likely require some drastic and long-term changes in our environmental and agricultural practices.

The Bees Are All Right - After years of uncertainty, honeybees appear poised to recover from collapse

http://www.slate.com/...lony_collapse_disorder_is_no_longer_the_existential_threat_to_honeybees.html

CCD was a real problem, probably six or seven years ago,” says Jeff Pettis, an entomologist whose research played a major role in uncovering the causes of CCD. He adds that

in the past three to five years, though, researchers in his field have as not seen much CCD and that globally honeybee populations are not in decline.

…

Queen honeybees regularly lay 1,500 eggs per day, and if the conditions call for it, can up that figure to as many as 2,000 eggs per day or more.

Even if honeybee keepers report losing as much 30 to 45 percent of their bees in a single year, this doesn’t actually mean the honeybee population will decline by that much. The beekeepers’ response will be to simply leverage the queens’ enormous reproductive abilities, which will quickly recoup those losses.

(US) Nation’s Beekeepers Lost 44 Percent of Bees in 2015-16

https://beeinformed.org/2016/05/10/nations-beekeepers-lost-44-percent-of-bees-in-2015-16/

“

The high rate of loss over the entire year means that beekeepers are working overtime to constantly replace their losses,” said Jeffery Pettis, a senior entomologist at the USDA and a co-coordinator of the survey. “These losses cost the beekeeper time and money. More importantly, the industry needs these bees to meet the growing demand for pollination services.

We urgently need solutions to slow the rate of both winter and summer colony losses.”

Seed coating with a neonicotinoid insecticide negatively affects wild bees

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v521/n7550/full/nature14420.html

seed coating with Elado, an insecticide containing a combination of the neonicotinoid clothianidin and the non-systemic pyrethroid β-cyfluthrin, applied to oilseed rape seeds,

reduced wild bee density, solitary bee nesting, and bumblebee colony growth and reproduction under field conditions. Hence, such insecticidal use

can pose a substantial risk to wild bees in agricultural landscapes, and the contribution of pesticides to the global decline of wild bees may have been underestimated.

COLOSS - Losses of honey bee colonies over the 2014/15 winter - Preliminary results from an international study

http://www.coloss.org/...ies-over-the-2014-15-winter-preliminary-results-from-an-international-study

A preliminary analysis of the data shows that

the mortality rate over the 2014-15 winter varied between countries, ranging from 5 % in Norway to 25 % in Austria, and there were also marked regional differences within most countries.

The overall proportion of colonies lost (including colonies with unsolvable queen problems after winter)

was estimated as 17.4 %, which was twice that of the previous winter.

a fajn studie z letoska, stoji za to precist aspon vypisky :)

Lost colonies found in a data mine: Global honey trade but not pests or pesticides as a major cause of regional honeybee colony declines

http://www.coloss.org/...t-pests-or-pesticides-as-a-major-cause-of-regional-honeybee-colony-declines

fulltext clanek studie:

zde

Historically reports about regional large scale losses of honeybee colonies are both recurrent and frequent, with dramatic events dating back to medieval times (Fleming, 1871).

Today mass losses can be typically linked to diseases or regional poisoning (Pistorius et al., 2009).

A prominent exception has been the so called colony collapse disorder (CCD) which killed millions of colonies in the US (vanEngelsdorp et al., 2009). In spite of considerable research efforts (Cox-Foster et al., 2007; Stokstad 2007)

CCD could not be clearly associated with a specific pathogen (Anderson and East 2008) or poisoning. As a consequence, interactions among pests, pathogens and pesticides were suspected to have caused these massive colony deaths.

…

colony losses can be regional extremely variable.

…

the losses rarely exceeded 30% at the national scale.

…

the loss of colonies can be disastrous for the individual apicultural operation, the number of lost colonies is much less relevant than the number of existing colonies from a societal or ecological perspective.

For Europe the densities of managed honeybee colonies have recently been reported to have fallen below one colony per square kilometre (Chauzat et al., 2013)

which is more than an order of magnitude less that the density of wild honeybees in the African Kalahari desert in regions without any beekeeping and rather unfavourable environmental conditions for honeybees.

…

the numbers of managed colonies have been officially documented for ca. 100 countries since 1961 in the global database managed by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

…

This data has been used before to document the

decline of honeybee colonies in Europe and the US over the past between 1961 and 2009 in spite of a global increase of colony numbers.

…

The global increase of colonies is insufficient to compensate for the even higher demand for pollination which by far exceeded the availability of honeybee colonies.

…

Globally there is a significant trend of colony increase of more than 60% over the past 50 years from 1961–2013 (Fig. 1). Clearly,

the globally collected data does not support the notion of a global colony decline. However, the variability among the reporting countries is huge, ranging from declines down to one forth to more than the four fold increase of the colony number as of 1961.

At a continental scale the most dramatic decline occurred in Europe between 1989 and 1995 where almost seven million colonies disappeared within only five years. This loss in managed colony numbers coincided with the collapse of the socialistic regimes in the Eastern European countries after 1989. (except Czechoslovakia and Hungary, where no significant colony decline was observed during this period.

…

the

arrival of the parasitic mite V. destructor in the early eighties (Potts et al., 2010b; Rosenkranz et al., 2010)

had no detectable effect on the number of managed colonies in the full European data set. On the contrary, the number of colonies in Europe increased from 21.4 Mio to 22.4 Mio between 1980 and 1990 (Fig. 1). So, although V. destructor has been clearly identified as the major pest and foremost factor in colony losses (Genersch et al., 2010; Potts et al., 2010a), it did not affect the number of managed colonies reported to the FAO at all.

…

… It shows how beekeepers efficiently adopt their operations to comply with the challenges set by pests even as lethal as V. destructor.

…

Western Europe has seen a less dramatic but constant and highly significant decline of colonies in the past three decades. At the average there was a 1% decline per year. …

This is nearly five times higher as the decline observed

in the US in the same period which suffers from a constant

decline of about 0.21% per year in the past two decades

…

other regions of the world show a fundamentally different development. The number of managed colonies more than doubled over the past 50 years at a rate of 2.5% per year in Southern Europe. An even steeper increase can be observed for South America (5.2 _ 0.20), Africa (3.3 _ 0.11) and Asia (4.4 _ 0.07). Extreme examples of colony increase in the past five decades include Myanmar (157-fold), Pakistan (7-fold), Senegal (35-fold), Syria (11-fold), Uruguay (9-fold) and Vietnam (17-fold).

…

atypical declines were again associated with grave socioeconomic changes. These include:

1) A dramatic decline of 66% of the colonies in Madagascar after 1977, subsequent to the political coup from which apiculture never recovered.

2) A 73% decline in Burundi during the civil war, a loss which has however rapidly overcompensated during the past decade with three times as many colonies today as in 1961.

…

None of the colony number dynamics of the past 50 years, neither increase nor decrease, show any relation to the arrival of novel pests or the use of novel pesticides or toxins in the respective countries. Even the use of the controversially discussed and now partially banned neonicotinoid agrochemicals did not cause any abrupt decrease in colony numbers in any of the national data provided nor did they impact on the long term changes in colony numbers which went up or down irrespective of the use or ban of pesticides in the data providing countries (Eisenstein 2015; Staveley et al., 2014). Yet it appears the long term declines, as shown for Western Europe and the US, are those of largest concern because they have been almost linear, consistent and stable over more than two decades.

These (EU&US) declines cannot be explained by pests, pathogens, pesticides or societal collapses and hence it may be helpful to use additional information to extract potential causes.

The honey data base

Globally the production has almost doubled over the past five decades

…

The data fall into two distinctly different groups: those countries with a colony decline and those with a colony increase. Countries with an increase in managed colonies show a positive slope between the change in honey production per colony and the number of managed colonies (b = 0.29 _ 0.64). Countries with a colony decline surprisingly have steep negative slope.

…

the more is imported also export increases showing that commercial honey trade takes an increasing share of the market. The negative correlation between colony number and production per colony implies that the yield per managed colony should have increased, in some of these countries more than doubled.

…

Given the reports that foraging conditions for bees have decreased rather than increased (Potts et al., 2010a), it seems unlikely that the enhanced colony productivity can be explained by bees working harder. If we assume that the biological capacity of a colony to produce honey has remained constant over time, and the foraging conditions have not become doubly rewarding, it is more likely that the honey marketing and/or colony management has changed. An extreme case may be that of the honey produced in Belgium. If one divides the honey produced by the number of managed colonies, Belgian honeybee colonies seem to globally excel with an average production of 83 kg per colony per year (average over the years 2009–2013). Such numbers are unheard of in Western Europe, where average honey yields per colony of 40 kg reflect excellent honey yield seasons (Genersch et al., 2010). At the same time the national Belgian honey production shows globally the highest correlation with the amount of yearly imported honey, one cannot exclude recurrent irregular reporting of imported honey as nationally produced to the FAO.

…

We found a highly significant negative correlation between honey trade and the corresponding change in the number of managed colonies (r = _0.55; P = 0.01, n = 20).

Countries suffering the strongest colony declines were those where honey trade became much more important than production.

…

Perhaps disappointing for some media,

the declines detectable in the FAO data set are not due to pathogens, pests, pesticides, climate change or any other factor of timely public interest. It is the decline in beekeeping activity and the increase of honey trade (Fig. 5) that is of concern. A global honey market with low honey prices in exporting countries may make it less attractive for professional beekeepers in importing countries to produce honey with their own colonies. This is well supported by the negative correlation between honey production and the number of colonies in countries with a colony decline (Fig. 4). Although, globally the honey production per colony increased by 16% per year over the past decades (1961–2013), with an average of 18.38 _ 0.35 kg (Fig. 6),

the reported steep increases in colony productivity in countries with colony declines are not likely to be real. Although improved management may have improved the efficiency of honey produc-tion and harvesting in many exporting countries, it is much more likely that the global increase in colony numbers is the primary driver of the increase of global honey produced. This is also supported by the significant increase in the variance of colony productivity among the various countries over the past decades (Fig. 6) which is strongly driven by the massive (and not necessarily plausible) increase in productivity per colony in the high honey trade countries.

…

It may now be time in the industrialized countries to reconsider policies on supporting apiculture.

In these industrialized countries it used to be the large number of hobbyist beekeepers that kept a few hives in the backyard that contributed the largest share in the number of colonies by far. To them the market value of honey may not be the prime driver for their operation. If the linear colony declines of the past 50 years in countries like the US, Germany, Austria and Switzerland continue at the current pace, in the following decades it may well fall below levels where we can only hope that wild bee pollinators, other than honeybees, can provide sufficient pollination services (Garibaldi et al., 2013). Given the reports on pathogens, negative impacts of pesticides and habitat loss of wild bee pollinators, this is probably an overly optimistic expectation (Fürst et al., 2014). In a few countries in Western Europe there are now first reports on increasing numbers of beekeepers.

Recent data from UK (Vanber- gen et al., 2014)

show how tightly the increase colony number is correlated by the number of beekeepers. The path back to the old colony densities in Europe and North America may have been reopened in response to the media attention of global honeybee declines. This is a very first positive signal that should be fostered by receiving more support from governmental institutions.

If this increase in the interest for apiculture has been partly due to the media hype on colony losses this is clearly to be welcomed, even though it may very likely be for different reasons than many media wanted the general public to believe.